Rutherford Scattering

Author: Tim & Eva

INTRODUCTION

It has been over a century since Ernest Rutherford interpreted the bizarre results of Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden’s scattering experiments: the atom has a small hard positively charged nucleus surrounded by an electronic system – the true birth of nuclear physics! This is known as the “gold foil” experiment. Ever since reading about it in the beginning chapters of Richard Rhode’s book, Making of the Atomic Bomb, I wanted to perform this “simple” experiment for myself.

I place simple into quotes because it is far from simple. “Hindsight is 20/20,” does not apply, even though I knew what I was looking for, it took a while to find it. The principle is simple, but the experiment is tedious for the amateur when outfitted with only a small alpha source.

Having successfully performed the experiment, with all sorts of fancy nuclear instrumentation, it is now almost unbelievable that it was successfully done in 1913 in the first place! Please do not misunderstand my statement, I am not denying that these great physicists performed this experiment, I know they did, but it is amazing that they did.

Given that their initial experiments were performed manually, in again, unbelievable experimental conditions: staring with the naked eye in a dark room at faint scintillations from limited intensity alpha sources for hours, days, months on end, I now understand Geiger’s motivation for inventing the Geiger Counter and the then subsequently Lorded Rutherford’s request for a “copious supply” of charged particles (simply put, a particle accelerator). I sure wish I had a 5MeV accelerator too.

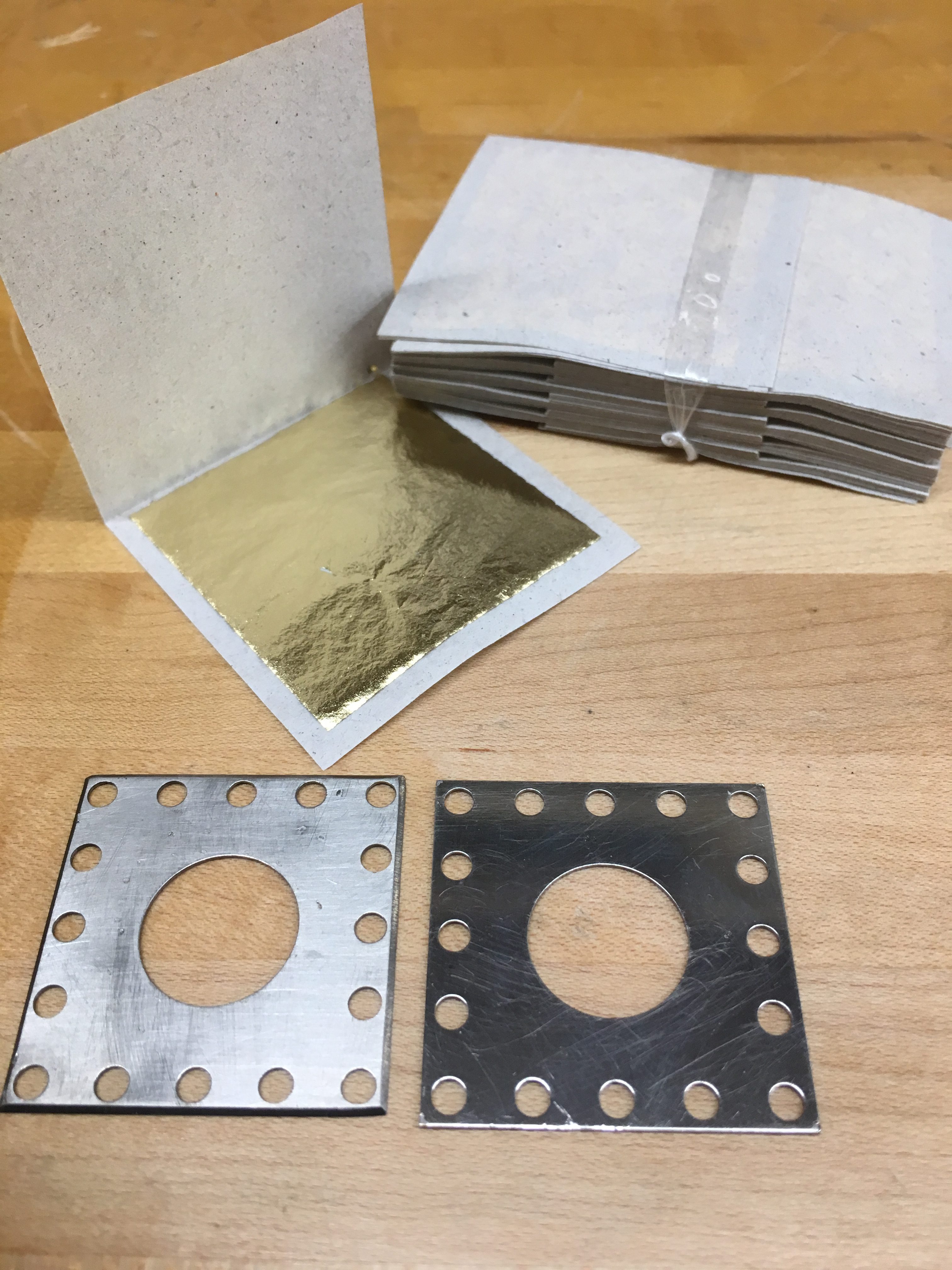

The experiment shines a thin beam of alpha particles onto an extremely thin metal foil, such as gold leaf used for gilding, and follows the path of the alpha particles passing through, more specifically, the angle that they scatter from interacting with the foil. The foil has to be of just the right thickness to present a sufficient number of atoms for the alphas to scatter off of in a reasonable amount of time, but not so thick to reduce the alpha energy below a detectable level or worse, causing the alphas come to a complete halt.

HOW THICK IS GOLD LEAF ?

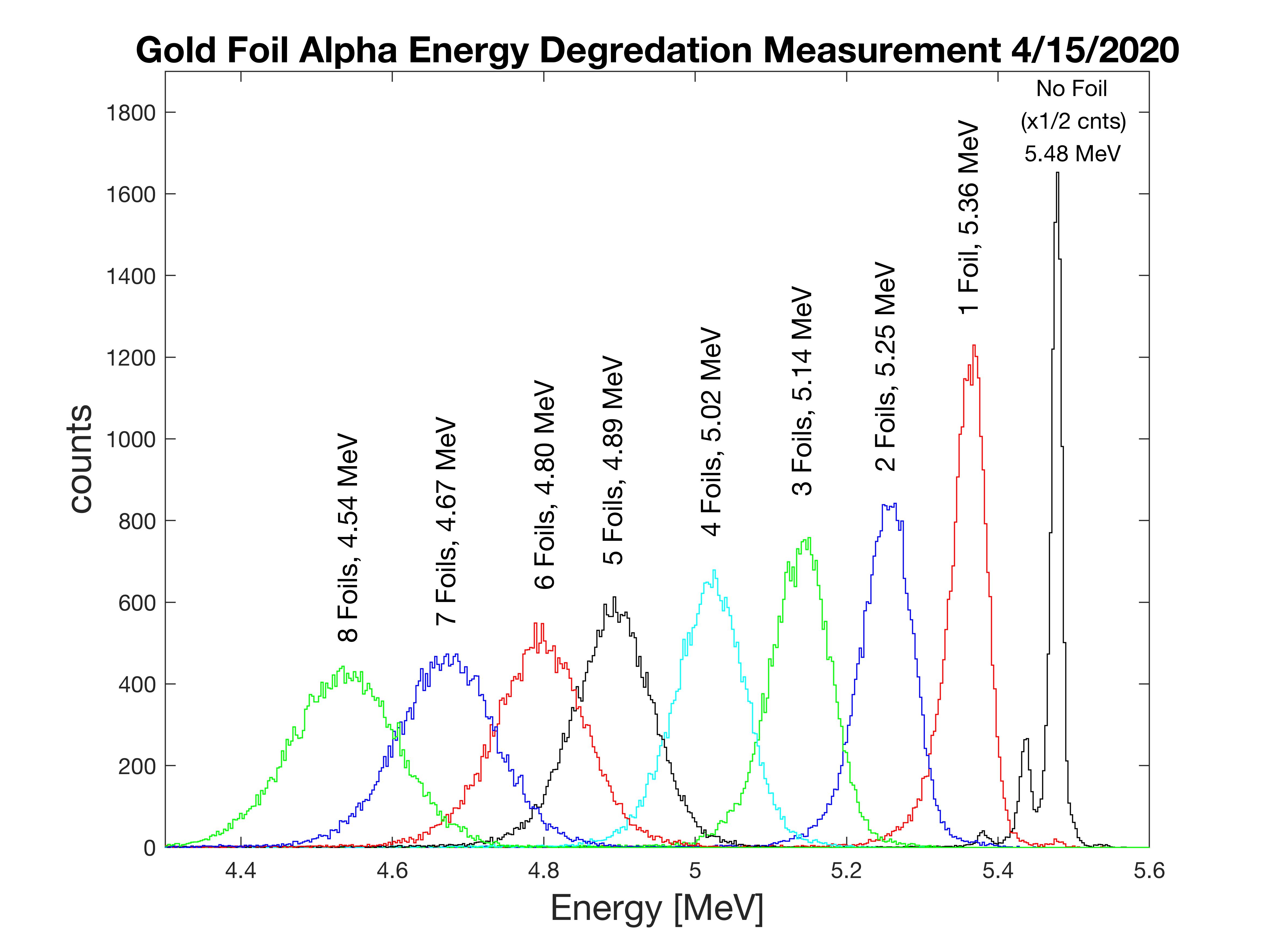

Alpha particles are bare helium nuclei, and hence are relatively massive nuclear projectiles. As an energetic alpha particle enters matter, it immediately begins to interact and slow down. Over short distances, (fractions of a micrometer) the energy loss per distance traveled is linear, we can write that as dE/dx. After traversing some thickness of matter, Delta-X, the alpha particle will have lost Delta-E of energy. By measuring the initial and final energies of the alpha particle beam passing through the gold foil, we can infer the foil’s thickness.

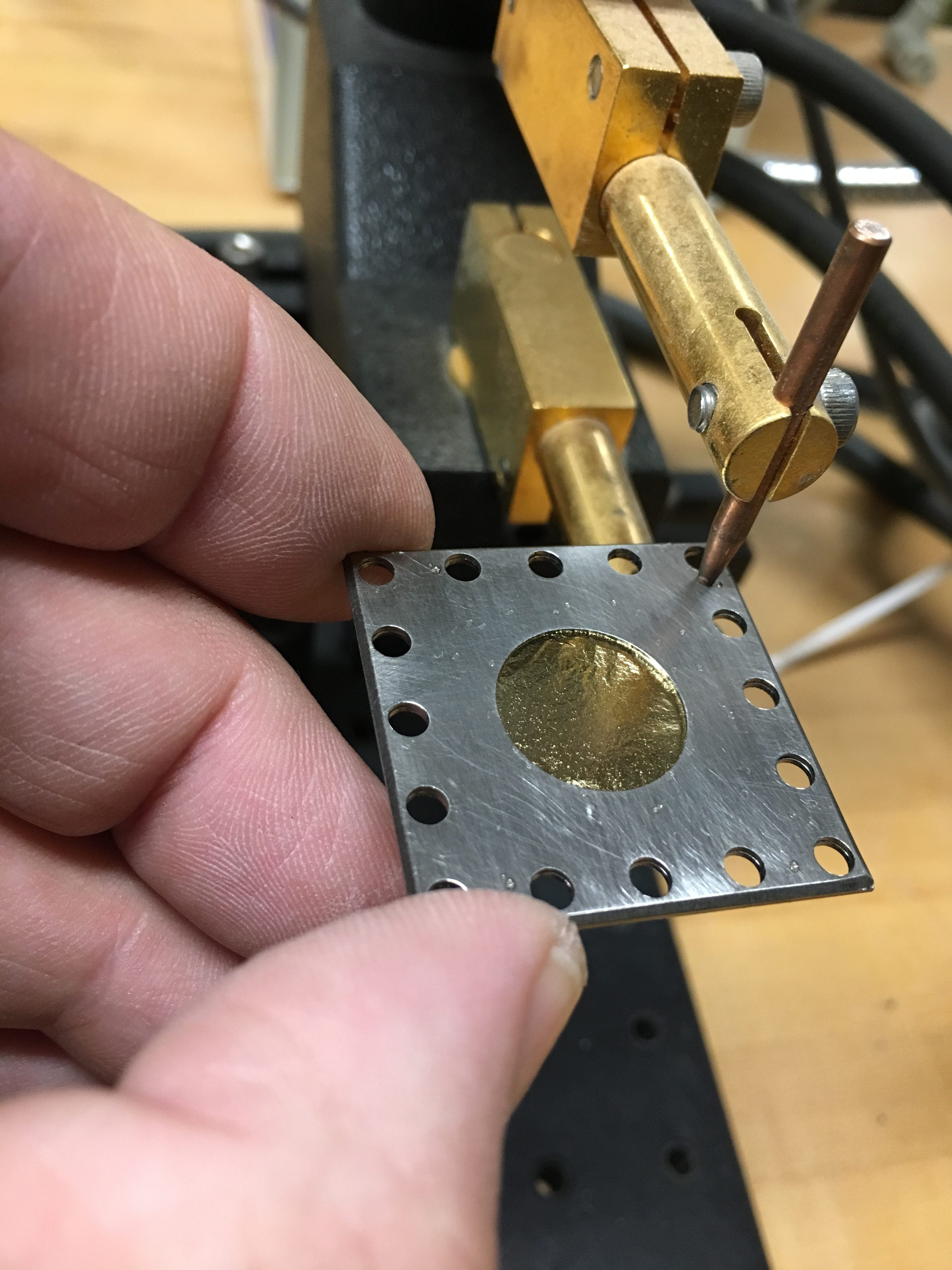

For my version of the experiment I ordered a 100-pack of 2×2-inch squares of gold leaf from eBay for $15. There was no information on the actual thickness, or mass per unit area of sheet, so the first step was to measure the foil thickness by alpha energy attenuation. I used my Ortec Alpha King NIM-based alpha spectrometer and a low level front-surface calibration source. One-by-one, I stacked up sheets of gold leaf into a demountable cassette that I placed between the alpha source and the detector. I acquired data for as long as needed to achieve 25,000 counts under the spectral curve for each additionally layer added. The following plot is the resulting data. It is interesting to note, not only the reduction in energy, but the increased width of the spectral line.

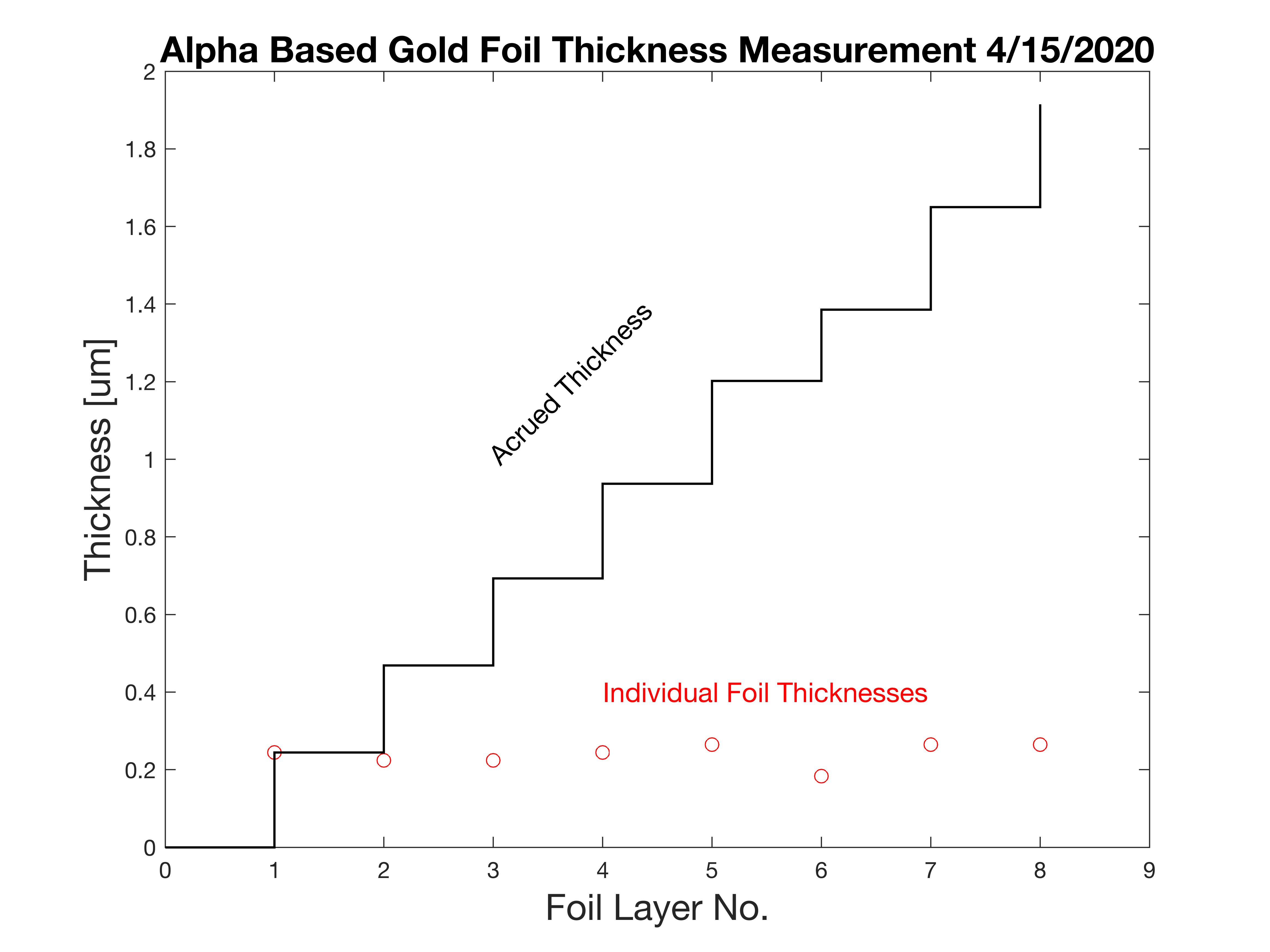

Using NIST look-up tables for alpha particle ranges in gold (dE/dx), given in units of MeV.cm2/g, knowing the change in energy per sheet in MeV, and the density of gold (19.3g/cm3), we can calculate the accruing thickness of the gold foil stack. There was some variation in a few sheets of the gold leaf sheets.

The alpha’s initial and final energy will be needed for analysis later on, so here is the same plot but with two different thicknesses of gold leaf foils added.

Eager to get started, I constructed the actual RBS gold foil target by using two more sheets of gold leaf, folded into quarters and stacked, producing a target 8 layers thick. I built this before I completed the previous measurement. In retrospect, I should have held off, as I then performed another thickness measurement by alpha energy shift and determined this arrangement was about 2.2um thick, too thick – most other RBS experiments use foils less than 1um thick, and as thin as 0.4um. Never the less, I proceeded to attempt the experiment with this thicker stack. It is worth noting that 7um of gold is sufficient to completely stop a 4MeV alpha particle. (Perhaps I will repeat this with a thinner foil).

SCATTERING EXPERIMENT

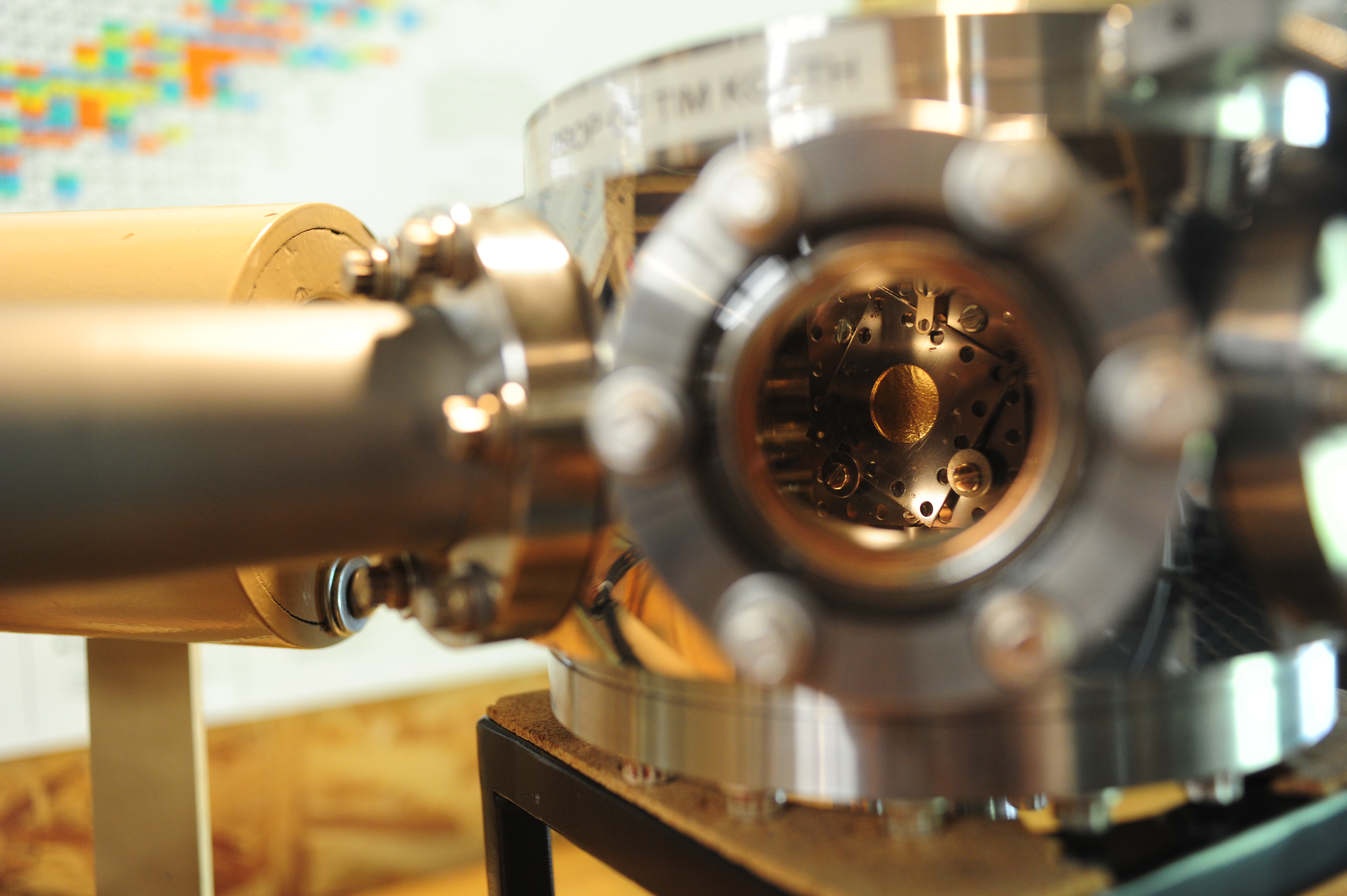

With exception of the gold leaf, the experimental apparatus made use of equipment and vacuum components that I have accumulated over two decades and have been lugging around ever since.

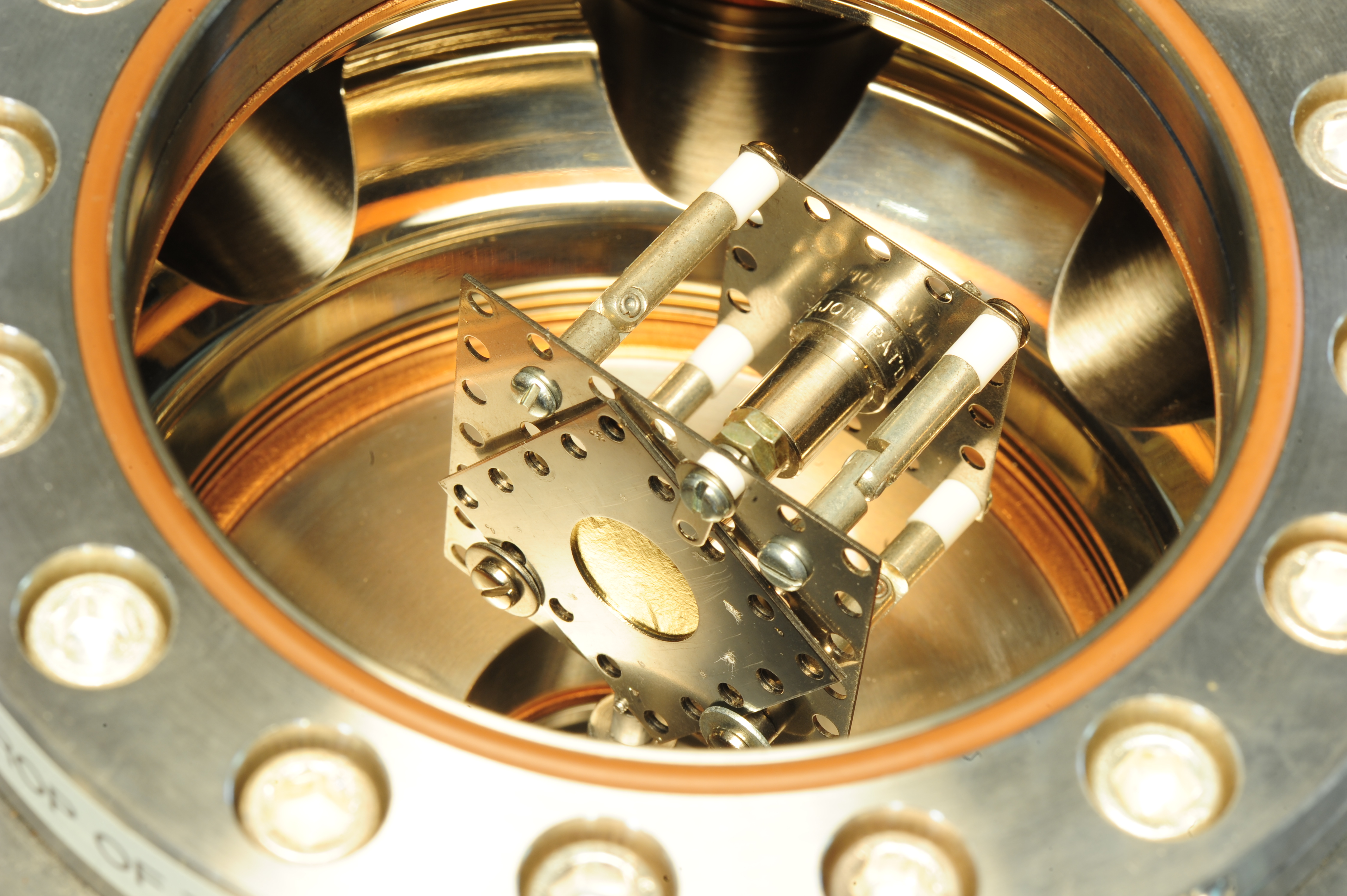

The scattering chamber is an octogonal chamber with two 6-inch con-flat (CF) ports on the top and bottom, and eight 2.75-inch CF ports on the side placed in 45-degree increments. Starting at the “3 o’clock” position in the above photo and rotating clock-wise the arrangement of the chamber is as follows: vacuum pumping port, with two valves in series to slowly pump the chamber so as not to rip the gold foil during pump down. Next, a variable leak valve for slowly bleeding up to atmosphere when venting the chamber, again, so as not to rip the gold. A CF blank directly facing us. Next a 2.75CF viewport, with it’s dark cover in place. Then, the alpha detector arm. Behind that is a lead shielded NaI(Tl) detector from the previous 237Np alpha-gamma coincidence experiment. In the back, another CF blank, and finally, a Pirani vacuum gauge sensor. The top of the chamber is outfitted with a load-lock door, and the bottom has a linear-and-rotary motion feed through for positioning the foil-source structure.

I decided to mount the alpha particle “beam” and gold foil “target” assembly together in a fixed framework that would rotate with respect to the alpha detector. This is very similar to the 1913 Geiger-Marsden setup (had I a larger chamber, I would have liked to make the rotation of the source, the foil, and the detector(s) all independent). The alpha source is mounted to a stainless steel Kimball Physics eV square plate having an aperture in the center. A cajon stainless steel pipe fitting was spot welded to the other side of the stainless steel plate, creating the beam collimator: the source active diameter is 0.1 inches, the inside diameter of the collimator is 0.19 inches, and its length is about 1.32 inches long, creating a source divergence cone of 12.3 degrees.

A shaft was mounted to the bottom of the foil target and alpha beam assembly such that it would rotate about the centerline of the gold foil cassette. It was connected to the linear/rotary motion feed through and vertically adjusted to be centered in the chamber.

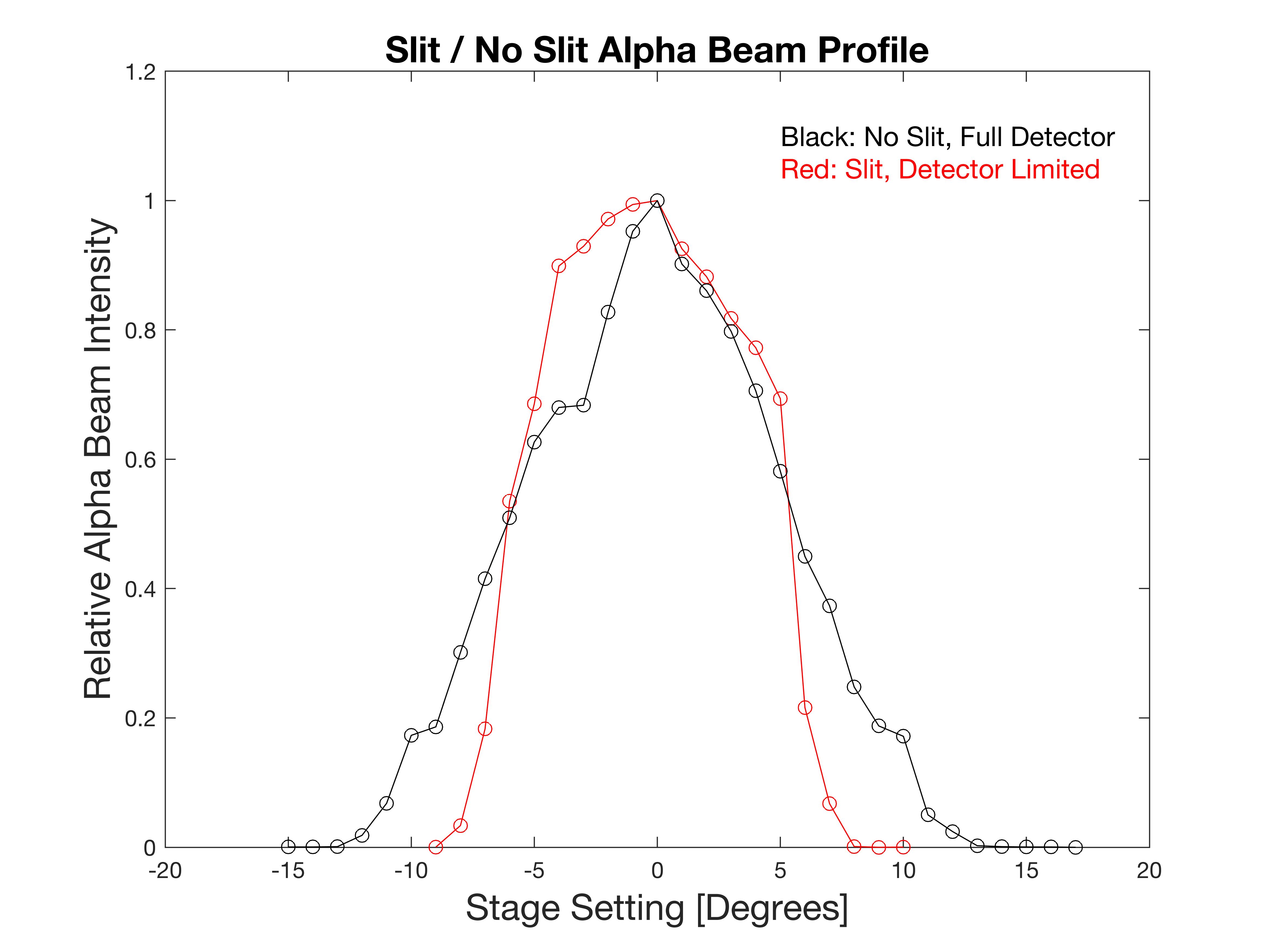

The alpha detector is an Ortec Si Surface Barrier Detector. At first I tried to improve the angular width by placing a slit on the face of the detector, making its azimuthal width about 2.5 degrees. The slits were removed since, as we will see, the alpha beam divergence itself was large, and the slits only reduced the counting rate without much benefit to angular resolution.

Two rotational scans were made without the target foil in place to determine the angular profile of the alpha “beam.” Clearly, without the slit on the detector face, the alpha beam was detectable as wide as +/- 12.5 degrees, which closely matched the expectation, the source divergence calculated to be 12.3 degrees, and the detector azimuthal “width” was also estimated to be 12.5 degrees, so edge-to-edge it is reasonable to see the width to be the sum of these two angle, or ~25 degrees (the black trace), The red trace is with the slit, of 2.5 degree width, would be 5 degrees summed with 12.3 degrees, or 17 degrees total.

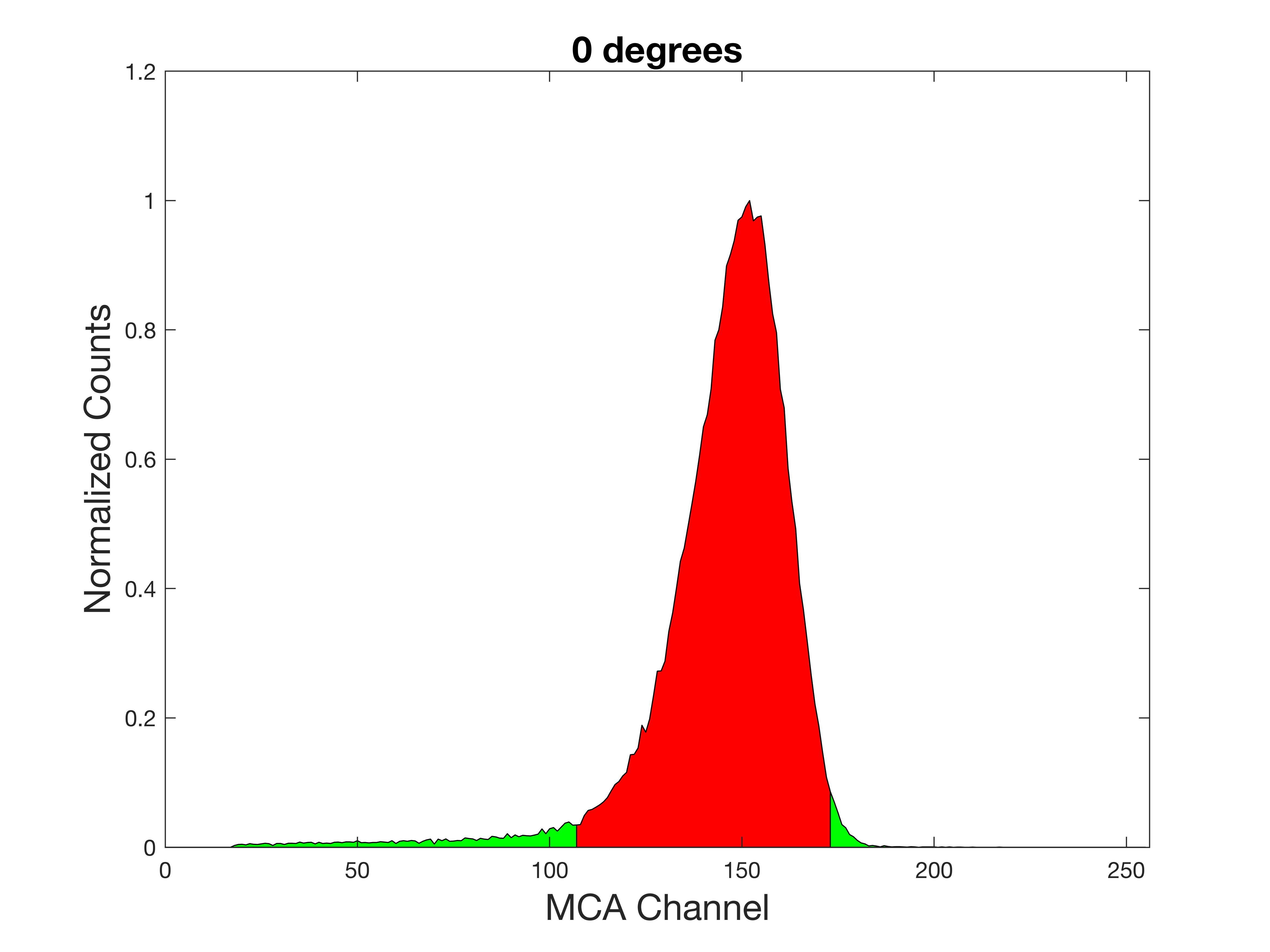

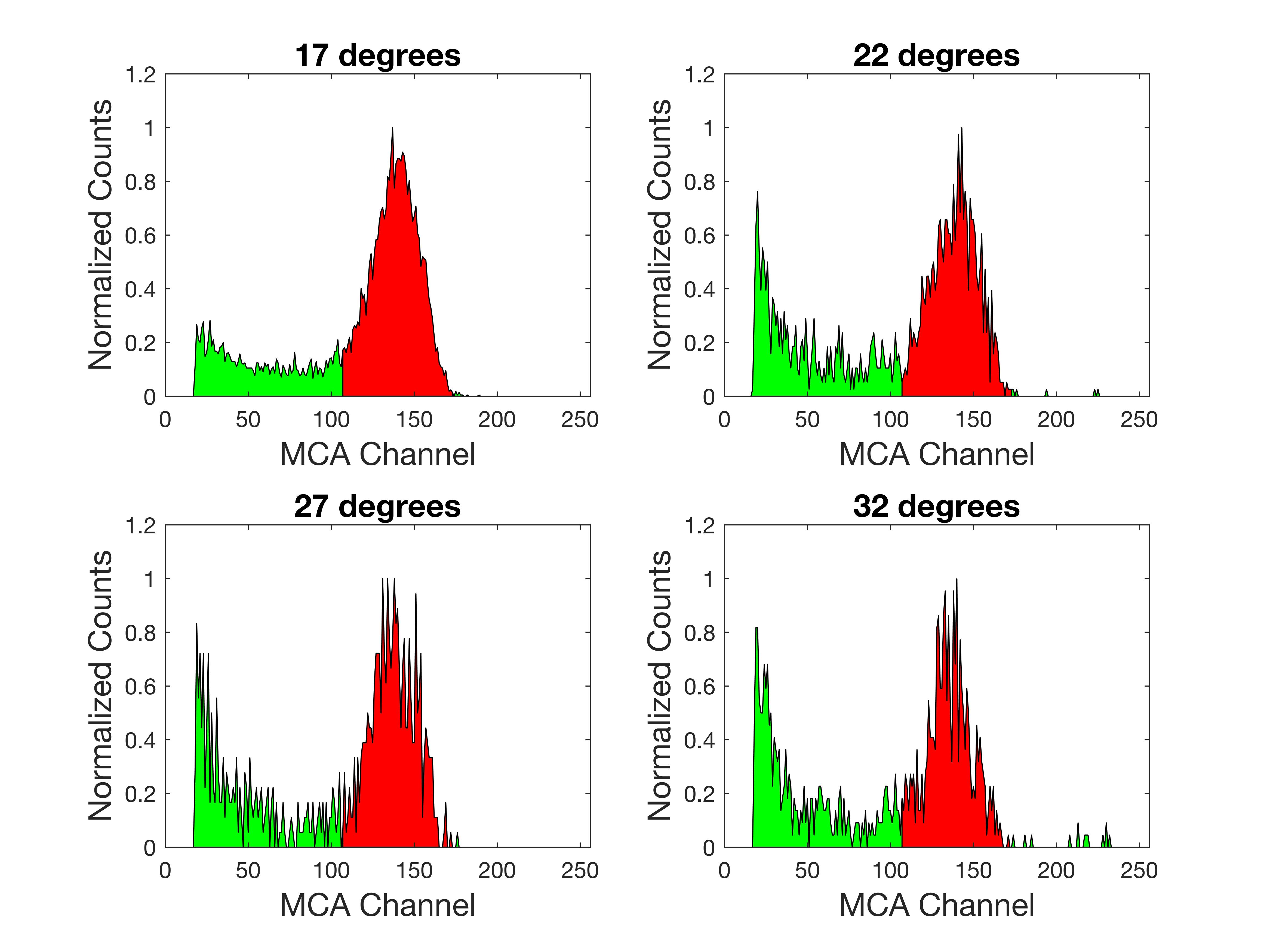

The no-foil beam width set the limits of small angle scattering to start at +/-17 degrees. The foil cassette was placed into the target-source structure and scattering acquisition commenced. The first data collected was at 0 degrees, head on, so as to set the MCA’s region of interest (ROI) to the lowered alpha energy peak. Only the events in this ROI are counted as scattering events. Since the scattering is considered inelastic, and the disparate masses of the alpha (4) and the gold (197), the alpha will lose an imperceptible amount from the actual scattering event, arriving at the detector with almost it full energy (less the dE/dx loss), allowing scattered signal to be isolated from background “noise.”

First, the source-foil structure was aligned with the detector (0-degrees) to be able to set up the region of interest:

Then the alpha scattering was measured at four angles, 17, 22, 27, and 32 degrees. As describe earlier, it would make little sense to measure less than 17 degrees, and 32 degrees found the limits of my patience (aka impatience). Due to the exponentially falling scattering probability with increased angle, acquisition took over 2 days to accumulate a mere 500 events at 32 degrees.

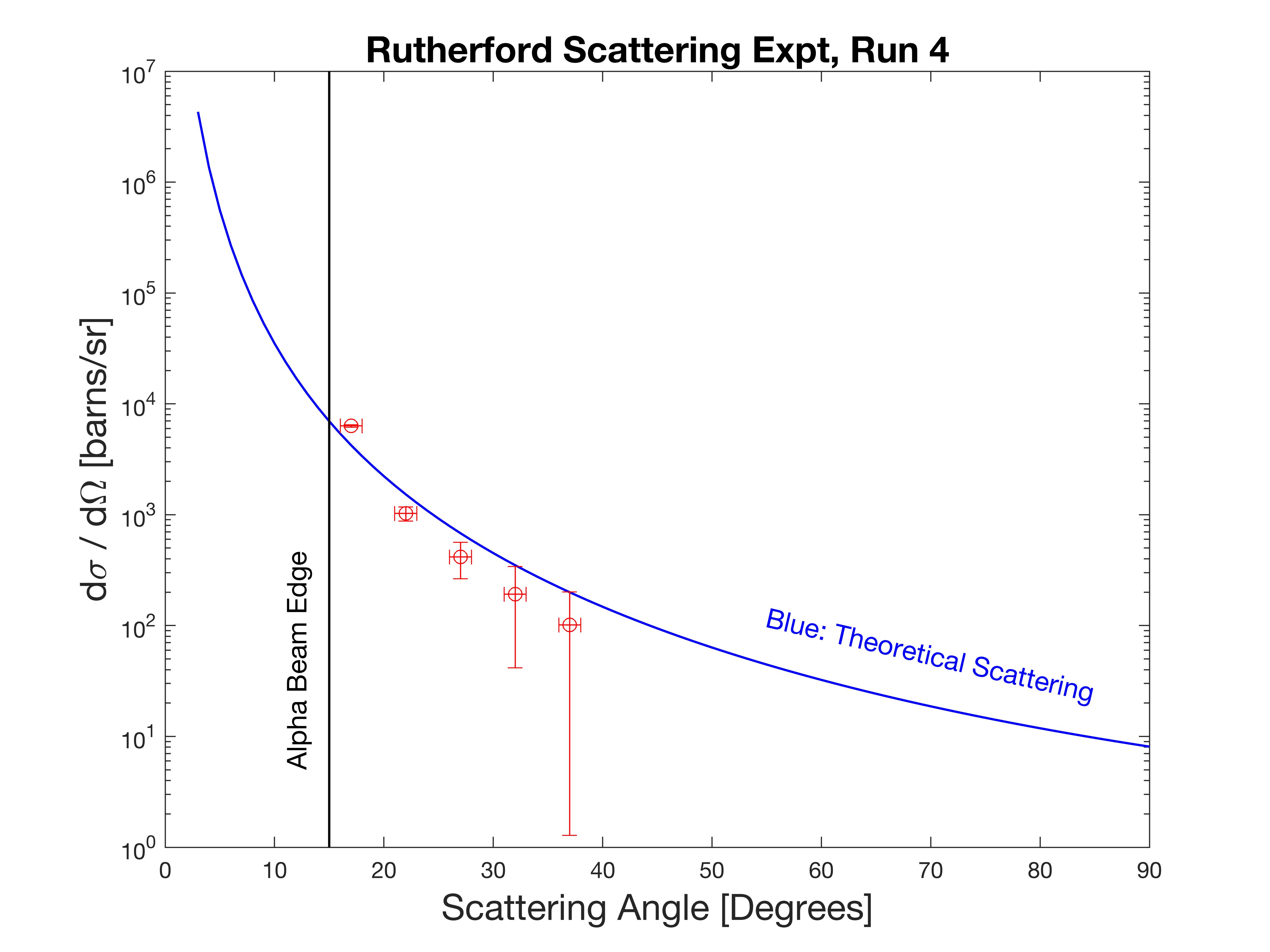

The interpretation of the data is pretty straight forward. The differential cross section, d/d

, is obtained from I/(Io *

o *

), where I is the scattering rate, Io is the incident alpha rate,

o is the number of gold atoms in the effective target volume, and

, is the solid angle of the detector in steradians [sr].

A measurement at 37 degrees took about 10 days, and has been added to the final data plot below. The five measurements, expressed as the differential scattering cross section, reasonably matches the theoretical trend. The absolute numbers on average fall below the calculate theoretical curve up to a factor of two. This I do not understand yet, but will continue to refine the measurement.

Conclusion, with enough time and surplus equipment, one can “bounce” alpha particles off of the nuclei of heavy atoms for themselves.

This has been one of the more rewarding amateur nuclear projects for me, not only because it was the defining nuclear experiment of probing the nucleus, but because I struggled to find what I know I was looking for. This in turn has given me an even deeper respect for Rutherford, Geiger, and Marsden’s research abilities. And especially for young Rutherford, who had to stand up against convention and let the scientific data be his confidence when breaking the news to the world.